Ihr Weg an die Humboldt-Universität

Aktuelle Nachrichten

Aktuelle Veranstaltungen

Studium an der HU

Das Studium an der Humboldt-Universität ist einzigartig: Es verbindet interdisziplinäre Bildung, Forschung und Praxis. In mehr als 170 Studiengängen bieten wir Studierenden eine frühe Einbindung in Forschungsprojekte, fördern das kritische Denken und den offenen Dialog über das Curriculum hinaus.

Studium an der HU

Das Studium an der Humboldt-Universität ist einzigartig: Es verbindet interdisziplinäre Bildung, Forschung und Praxis. In mehr als 170 Studiengängen bieten wir Studierenden eine frühe Einbindung in Forschungsprojekte, fördern das kritische Denken und den offenen Dialog über das Curriculum hinaus.

Forschung & Lehre

An der Humboldt-Universität gehören Forschung und Lehre – ganz im Sinne unserer Namensgeber – untrennbar zusammen. Dieses Prinzip gilt ausdrücklich auch für Wissenschaftler*innen in frühen Karrierephasen, die früh Verantwortung in Forschung und Lehre übernehmen können. Die HU ist eine exzellente Forschungsuniversität, die national und international in vielen Bereichen Spitzenleistungen erbringt.

Forschung & Lehre

An der Humboldt-Universität gehören Forschung und Lehre – ganz im Sinne unserer Namensgeber – untrennbar zusammen. Dieses Prinzip gilt ausdrücklich auch für Wissenschaftler*innen in frühen Karrierephasen, die früh Verantwortung in Forschung und Lehre übernehmen können. Die HU ist eine exzellente Forschungsuniversität, die national und international in vielen Bereichen Spitzenleistungen erbringt.

Open Humboldt

Unter dem Motto Open Humboldt teilen wir unser Wissen, unsere Expertise und Infrastrukturen über die Campusgrenzen hinaus. Dabei stehen wir in ständigem Austausch mit Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft. Wir möchten Menschen informieren und inspirieren, Partizipation fördern und ermöglichen.

Open Humboldt

Unter dem Motto Open Humboldt teilen wir unser Wissen, unsere Expertise und Infrastrukturen über die Campusgrenzen hinaus. Dabei stehen wir in ständigem Austausch mit Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft. Wir möchten Menschen informieren und inspirieren, Partizipation fördern und ermöglichen.

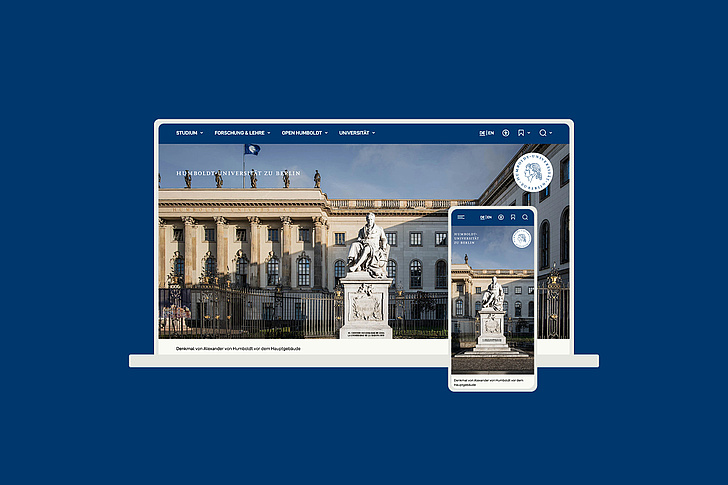

Unsere Universität

Die Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin verbindet wissenschaftliche Exzellenz mit gesellschaftlicher Verantwortung. Geleitet vom Erbe Humboldts steht sie für freie, unabhängige Forschung, forschendes Lernen und einen offenen Wissensaustausch mit der Gesellschaft. Sie bietet Raum für Vielfalt, kritische Debatten und neue Perspektiven – mitten im Herzen Berlins, weltweit vernetzt.

Unsere Universität

Die Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin verbindet wissenschaftliche Exzellenz mit gesellschaftlicher Verantwortung. Geleitet vom Erbe Humboldts steht sie für freie, unabhängige Forschung, forschendes Lernen und einen offenen Wissensaustausch mit der Gesellschaft. Sie bietet Raum für Vielfalt, kritische Debatten und neue Perspektiven – mitten im Herzen Berlins, weltweit vernetzt.